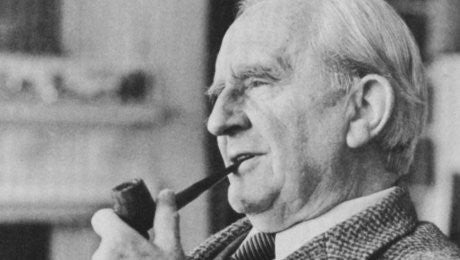

Professor Tolkien Goes to Mass: What the Author and Scholar Saw that Others Dismissed

I vividly remember going to church with him in Bournemouth. He was a devout Roman Catholic and it was soon after the Church had changed the liturgy from Latin to English. My Grandfather obviously didn't agree with this and made all the responses very loudly in Latin while the rest of the congregation answered in English. I found the whole experience quite excruciating, but My Grandfather was oblivious. He simply had to do what he believed to be right…"[i]

In such fashion, the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings stood firm against what fellow English author Evelyn Waugh called “a bitter trial.”

What went into the making of such a Catholic figure like Tolkien, who stood for the traditional Faith when nearly everyone around him acquiesced to the novelties or left the Church altogether? British Catholics in the 1960s were well-positioned to recognize how the techniques used by Cranmer five centuries earlier to impose Anglicanism on the English people were again being visited on men and women in the pews. Even so, most Catholics felt obliged to do as the authorities told them. Why was Tolkien able to discern the problems with the new Mass when most others were not?

Cradle Convert

Tolkien was introduced to prolonged hardship for the Faith at an early age. Born into a Protestant family, when he was three his father died, and when he was eight his mother Mabel converted to Catholicism with her two sons. As a result, relatives refused the widowed mother financial assistance, and four years later she died of acute diabetes. Tolkien later wrote:

My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labor and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.”[ii]

Raised afterwards in poverty by a capable and kind guardian – the Welsh-Spaniard Fr. Francis Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory – Tolkien developed pious habits he would keep throughout his life of frequent Mass, regular confession, daily prayers, hope in the efficacy of the Sacraments, and trust in the Church’s Magisterium.

Gifted at Language and Storytelling

From a young age Tolkien demonstrated remarkable ability at reading and speaking languages. By his teen years he had mastered Latin and Greek, and he soon developed proficiency in modern and ancient tongues, notably Gothic and Finnish. For his private enjoyment, he began to invent his own languages; years later he would invent his fictional Middle Earth to provide a homeland with its own history and heritage for his invented languages. He became professor of Old and Middle English at Oxford University, adding to his repertoire Spanish, Italian, Middle and Old English, Old Norse, and contemporary and Medieval Welsh; he also became conversant in ancient Germanic and Slavonic languages.

His fascination and love for languages led him to specialize in the field of philology, which he dealt with the words which make up a language, not merely to learn their meaning, but to find out their history. Meaning and history are discovered by studying language, literature, culture, theology, and mythology to uncover the source or origin and the themes common to them all. Philology provided Tolkien with a moral and philosophical framework for treating language that was consistent with his Catholic Faith, one that could be used to find in all stories echoes and reflections of the Gospel story.

Myths and fantastic stories

Tolkien’s love of languages and stories, elevated by his Catholic Faith and conditioned through his education and training, also manifested itself in a love for mythic tales. This was not simply because the mythic stories were engaging or amusing, but because they echoed elements of the Gospel story itself. Coining the term “eucatastrophe” to describe the sudden turn of events in a story that change it from a great tragedy to a joyful recovery, Tolkien explained the concept thus:

The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: ‘mythical’ in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. It has preeminently the ‘inner consistency of reality.’ There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath.”[iii]

Just and language has rules, so do stories. Arbitrariness, shallowness, banality, lack of fidelity, amateur treatments – these failings spoiled both language and stories. Against this Tolkien put his Catholic Faith and all that was consonant with it.

Dangers of Aggiornamento and Ecumenism

In a letter to his son Michael dated August 25th, 1967, Tolkien commented directly on the matter of the new Mass:

The 'protestant' search backwards for 'simplicity' and directness - which, of course, though it contains some good or at least intelligible motives, is mistaken and indeed vain. Because 'primitive Christianity' is now and in spite of all 'research' will ever remain largely unknown; because 'primitiveness' is no guarantee of value, and is, and was in great a reflection of ignorance. Grave abuses were as much an element in Christian liturgical behaviour from the beginning as now. (St Paul's strictures on Eucharistic behaviour are sufficient to show this!) Still more because 'my church' was not intended by Our Lord to be static or remain in perpetual childhood; but to be a living organism (likened to a plant), which develops and changes in externals by the interaction of its bequeathed divine life and history - the particular circumstances of the world into which it is set. There is no resemblance between the 'mustard-seed' and the full-grown tree. For those living in the days of its branching growth, the Tree is the thing, for the history of a living thing is part of its life, and the history of a divine thing is sacred. The wise may know that it began with a seed, but it is vain to try and dig it up, for it no longer exists, and the virtue and powers that it had now reside in the Tree. Very good: but in husbandry the authorities, the keepers of the Tree, must look after it, according to such wisdom as they possess, prune it, remove cankers, rid it of parasites and so forth. (With trepidation, knowing how little their knowledge of growth is!) But they will certainly do harm if they are obsessed with the desire of going back to the seed or even to the first youth when it was (as they imagine) pretty and unafflicted by evils. The other motive (now so confused with the primitivist one, even in the mind with any one of the reformers): aggiornamento: bringing up to date: that has its own grave dangers, as has been apparent throughout history. With this, 'ecumenicalness' has also become confused."[iv]

Tolkien saw the grave problems of the conciliar changes: not just because he knew his Faith intellectually, but because he recognized that what was being done to the language of the Mass was a great infidelity that had no power to bind because it had no root in the ancient source Himself. As the younger Tolkien had said years earlier, “no half-heartedness and no worldly fear must turn us aside from following the light unflinchingly.”[v]

[i] Published in The Mail on Sunday (2003), by Simon Tolkien

[ii] J.R.R. Tolkien Biography: Life of Tolkien (2002), by David Doughan, p. 31.

[iii] On Fairy-Stories in Essays Presented to Charles Williams (1947), by J.R.R. Tolkien.

[iv] Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, (1981), Ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien, no. 306.

[v] Tolkien: A Biography (1977), by Humphrey Carpenter, p. 73.

Also in News from Tradition

Death of Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais

Prayer Intention for Bishop Tissier de Mallerais

We ask for prayers for His Excellency Bishop Tissier de Mallerais.

On the morning of Saturday 28 September, after the Angelus, he fell on the stairs of the seminary in Ecône and lost consciousness. He is currently in hospital.

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre on the Feast of Christ the King

The following sermon for the Feast of Christ the King was delivered by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, founder of the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), on October 29, 1989 in Dublin, Ireland.

Today we must pray to Our Lord Jesus Christ, we must pray to the Blessed Virgin Mary to remain true Catholics and to do everything possible to become saints. We must come to church frequently, pray in our church, receive the graces of the sacraments in order to become saints, to sanctify our souls and to go to heaven with all the members of our families and all those who kept the Catholic Faith here on earth and now enjoy the happiness of heaven.

Brent Klaske

Author

Director of Operations at Angelus Press. I have worked in Catholic publishing for more than 20 years. I currently live near St. Marys, KS with my wife and 10 children.